DaVinci Resolve is a wonderful piece of software for editing and processing video, and is available to anyone for free. However, it is designed for professionals, not (us) amateurs. So, support for consumer file formats is sparse, and what is there can be picky. That doesn't mean consumers cannot use DaVinci Resolve with our footage, but it does mean we need to process our video and audio before we can import it into DaVinci Resolve. Here are my best suggestions for speed and quality.

IMPORTANT NOTE: Decoding and re-encoding video (or audio) WILL degrade the quality. Unless you are actually modifying the video, avoid re-compressing your content. And if a tool says it is converting the video (especially if the resolution, format, or CODEC is being changed, and usually if the tool takes a long time and/or displays frames during the conversion), it is most likely decoding and re-encoding. This guide provides information on how to process video into formats compatible with DaVinci Resolve without re-encoding.

Tools

I'll mention use of specific tools below. Here is the list with links:

Video

Before I go any further, you should be familiar with the concept of a CODEC and a container. Please visit this blog post for a quick discussion. But if you are already familiar, please read on.

DaVinci Resolve (and Fusion) is primarily designed to work with files containing video that is uncompressed or lightly compressed. Consumers are unlikely to have even heard of the most common professional formats (DNxHD, ProRes, etc.), let alone used them. But that's what professionals use, and that is the target (paying) customer base for DaVinci Resolve.

However, us amateurs don't have cameras that produce video in those formats. Plus, we don't have budgets for the computer systems these formats demand. Instead, most modern consumer devices use one of the variants of the MPEG-4 compression algorithm. The camera will use a CODEC to compress the video and audio, and then store these two "streams" into a file on your SD card.

The problem starts here, because DaVinci Resolve doesn't understand all the container formats a consumer camera might use, even though it usually understands the data inside them. To make matters worse, all the cameras don't package the data into the container file in the same way. Presumably, all of these files comply with a specification, but DaVinci Resolve wasn't designed for this, so it isn't happy with some variations.

To throw us another curve ball, due to file size limitations of consumer devices (usually the filesystems in use on computer hard drives), longer recordings are typically broken up into multiple files. Unfortunately, I haven't found any of these multi-file recordings that DaVinci Resolve likes as-is.

Repackaging vs Re-encoding

NOTE: There are lots of software applications out there that can convert videos from one format to another. But BEWARE: Most of them actually decode the encoded data and re-encode it. This introduces another, needless layer of loss into the process, degrading your (already consumer-quality) video. So it's a very good idea to avoid this. Software that simply repackages the data into a different container is much preferable.

Repackaging software can be difficult to find and cryptic to use. And all repackaging software isn't created equal. Unfortunately, DaVinci Resolve still isn't happy with repackaging results from some programs.

I don't claim that the software applications below are the only software that works with DaVinci Resolve, but after trying a bunch, I've found these do work for me.

AVCHD

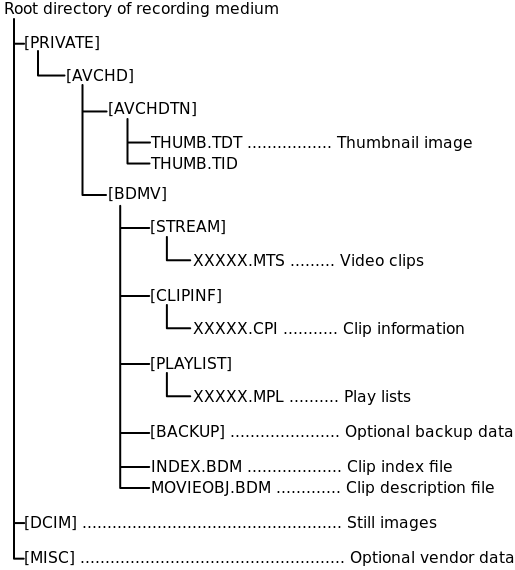

AVCHD is a format that most consumer FHD (full HD -- i.e. 1920x1080) camcorders use for recording. On your storage device (usually an SD card) there will be a directory structure similar to the one shown here (that for some bizarre reason starts with a PRIVATE directory):

Please Note: Software will usually accompany your camera to allow you to import these recordings to your computer. I'll be honest...I don't ever used that software. I installed software that came with my very first digital camera, and I will never do so again. It was old, slow, buggy, cumbersome to use, installed way too many packages that I would never use, and tried to take over my computer (well, it overwrote all my file associations, so just viewing an image, whether it came from the camera or not, always loaded the huge, slow to open package, which felt like it took over my machine). If you are comfortable with that software (and it works with your operating system), that may be a viable option for you. If not, read on...

AVCHD uses a more complicated part of the MPEG-4 specification (part 10), requiring more powerful processing by the camera. The result is better quality with smaller file sizes.

In researching the AVCHD format, and in authoring AVCHD discs myself (the poor man's Blu-Ray, which are normal DVDs, but which contain HD video content that most Blu-Ray players can play), I can tell you that AVCHD can provide a lot of features beyond just storing video. But in my experience with several camcorders, other than the thumbnails used to show the clips while in the camera, there's only really one feature that the AVCHD directory structure itself provides:

AVCHD video at the bottom of the directory tree shown above, is stored in MTS files inside the STREAM directory. MTS is one of several file extensions for the MPEG-2 transport stream (others are M2TS, TS, or sometimes VOB, but AVCHD uses MTS). The MPEG-2 transport stream container can hold a number of different types of streams (and it can hold multiple streams, like video, different language audio tracks, subtitles, etc.), including an MPEG-4 compressed stream. That's what it holds in an AVCHD recording. Specifically, the video stream is an MPEG-4 Part 10 stream, also known as h.264 or AVC (Advanced Video Codec).

DaVinci Resolve is happy with MTS files containing h.264, but there are two issues:

- MTS files are typically limited to 2 or 4 GB to stay compatible with older filesystems. (i.e. when a customer copies the files to their computer, if the files are too big, they won't copy, and the customer will be confused and angry). However, the breaks in MTS files (at least on the Canon and Panasonic camcorders I've tested) are made in mid-stream! There is some MPEG-4 sub-structure to where the break occurs (it's not at a completely random place), but it does seem to occur in mid-frame. This means that playing a second, third, or later file will result in some lost frames at the start. In some cases the later files may fail to play at all. The latter is the case with DaVinci Resolve. Each file typically holds 10-20 minutes, so this is something very likely to affect you, if you record longer than this.

- The audio format may be incompatible with DaVinci Resolve. See this blog post for information on that issue.

Multiple Files

So, dealing with issue 1 above basically boils down to two possible solutions:

- Use the software that accompanies your camcorder to import the files to your computer. As I mentioned above, I don't do this, so I can't say how this works, or what format the resulting files will be on your computer hard drive. However, I will say it's highly unlikely that the software will be compatible with Linux, if that's your operating system of choice. So...

- Join the files yourself (even in Windows), which is what I do.

Joining the files on your computer is extremely simple for MTS files. Suppose you have copied the following files from the PRIVATE/AVCHD/BDMV/STREAM directory of your SD card:

00785.MTS 2,044,889,088 Oct 20 2015 6:35:22PM

00786.MTS 2,045,165,568 Oct 20 2015 6:52:02PM

00787.MTS 2,045,054,976 Oct 20 2015 7:08:34PM

00788.MTS 2,044,766,208 Oct 20 2015 7:25:04PM

00789.MTS 579,170,304 Oct 20 2015 7:41:26PM

Windows -- Utilize the command line copy command to concatenate the files:

copy /b 00785.MTS + 00786.MTS + 00787.MTS + 00788.MTS + 00789.MTS vid.MTS

Linux -- Utilize the command line cat command to concatenate the files:

cat 00785.MTS 00786.MTS 00787.MTS 00788.MTS 00789.MTS > vid.MTS

MP4

The MPEG-4 format is so flexible (and complicated) that its creators (the Motion Pictures Expert Group) broke it into a number of pieces and parts. At the time it was published, accomplishing the most innovative and aggressive portions would have been technically and/or financially infeasible, particularly for consumer products (i.e. products amateurs can afford). Full implementation would require too much CPU power, too much memory, too much speed from the CPU or memory, etc. So divisions in the specification allowed vendors of devices to create products that followed easier or simpler parts of the MPEG-4 specification. Later, the more complicated sections could be handled, as hardware capability increased and costs fell.h.264 (MPEG-4 Part 10) is the most ambitious of the spec (and even it has subdivisions that give some flexibility to vendors), and is what is used in AVCHD. Early devices couldn't handle h.264 for high resolutions. Some devices could handle h.264 for standard definition, but not HD (1280x720). Some could handle it for HD, but not FHD. But, for the most part, FHD video devices today can handle h.264 (to varying quality levels).

However, UHD (ultra high-definition -- 3840x2160), which is 4 times the size of FHD, pushes the processing requirements even higher. So, many devices today drop down to less complex MPEG-4 for UHD to keep "4K" consumer products affordable. This results in simpler compression, which is less efficient. And that gives either higher data rates for similar quality to h.264, or lower quality for similar data rates. When stored, these files typically use the MPEG-4 container format and the MP4 extension.

DaVinci Resolve is happy with MP4 files containing MP4 compession, but as with h.264, it is not happy with the way long recordings are divided into multiple files.

Multiple Files

Again, the 2 or 4 GB limitation of some consumer file systems is anticipated by many devices, so they break up the recordings into multiple files. With 4x the number of pixels, and less efficient compression, the individual files tend to contain much less time than MTS files (usually less than 10 minutes). So it's even more likely you'll see multiple files for a single recording. But unfortunately, the same technique used to concatenate MTS files does not work for these MP4 files.

To join MP4 files, things get a bit more complicated. It's still true that the second and later files are not fully independent, so reading them will result in lost frames at the start. But the method of breaking up the files differs, so raw concatenation does not work. However, I have found a tool that properly reconstructs the stream (albeit slower than simple concatenating):

mp4box (see tools above) is available for all the major platforms (although as of this writing, Mac support appears to be source only), and would concatenate three MP4 files like this:

mp4box -add file1.MP4 -cat file2.MP4 -cat file3.MP4 out.MP4

Compatibility

Unfortunately, the above process sometimes isn't all that is needed. As mentioned above, DaVinci Resolve is picky about what it imports. I assume the issue lies mostly with the Quicktime CODECs it uses (and I desperately hope BlackMagic Designs will drop Quicktime in favor of ffmpeg CODECs, now that even Apple has dropped support for Quicktime on Windows), but regardless of why, some MP4 files just won't load into DaVinci Resolve (or Fusion).

Repackaging in a container seems to be a black art, and I would have expected that most tools I found would have done a decent job of this, since they are likely to be following the spec. However, I've only been able to get mp4box, used in the following way, to get these problem MP4 files to be accepted by DaVinci Resolve (and Fusion).

mp4box -add in.mp4 -raw 1 -new temp

mp4box -add temp_track1.h264 -new out.mp4

(Note that it is possible to repackage through ffmpeg or mp4box in a single step, but I have found that DaVinci Resolve is NOT happy with the results. Please let me know if you find a one-step process that is compatible.)